-

ARTIST PROFILE: RON ISAACS

Trompe l'oeil MasterAN INTERVIEW WITH RON ISAACS

AF: Can you tell me about the trajectory of your art career?

RI: My parents were from eastern Kentucky, very rural, and they moved to Cincinnati before I was born. I was born in Cincinnati in 1941 and started drawing fairly early. And for some reason, we’ve never figured out why, when anyone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up I never said anything but an artist. I don’t know where it came from or why. But at any rate I never questioned it. Didn’t even go through the cowboy stage or the fireman stage or anything.

My parents moved back to Kentucky when I was 12. I had no opportunity to take art in high school at all. What I did was self-taught until I got to college. I went to Berea College in Kentucky and majored in art there and then went on to grad school at Indiana University and majored in painting. So I was trained as a painter.

About 1970, while I was working on canvas as a normal painter would, I happened to get the idea of attaching a piece of sawed out plywood to the surface of the canvas with an image on it to add another level and a little bit more interest. After I did about three of those, painting images on the surface of the cutout wood, I said why do I need the canvas? I can make any shape I want! So that was my big epiphany and eureka moment and I started sawing out everything and layering them first.

I was doing figurative imagery at the time, based on magazines, newspaper, photographs and other sources. I was stacking things, lots of multiple images. And eventually that led to an improvement in craftsmanship and learning to construct things out of many pieces of wood, trying to make relief sculpture. These were then painted and the trompe l’oeil things came along, you know ‘fool the eye’. Garments were my first subject matter for that, filled often with figurative imagery pouring out of them or other things.

AF: And when was that?

RI: This was the early 70s, about 1972. I think the first piece was my own raincoat. It took me forever to try to build it out of 3/8 inch regular domestic plywood, which is pretty raw stuff. Lots of cheap filler and so on. Eventually I discovered Finnish birch plywood, which is much higher quality with no fillers and many layers. That was a big step up in improvement. That’s what became my career, basically, are these relief constructions. I now define them as being almost exactly halfway between painting and sculpture. I used to have a sculpture friend who would kid me that someday I was going to invent sculpture all by myself.

I sort of did because I stumbled in through the back door, I think. It’s still hard for me to think of myself as a woodworker or as a wood craftsman at all because I’m still making surfaces to hang paint on. I sometimes have to define myself as a sculpture or a painter. The works came out of painting but they really are exactly halfway between. That breaks down into the division of labor too, because it usually takes about half the work to construct and half the work to paint. Some are harder to build, some are harder to paint. The idea is to translate flat panels or sections of birch plywood of various thicknesses into something that flows, behaves, like fabric or leaves. That’s just my way of working that evolved out of the original imagery.

Ron Isaacs, TROUSSEAU, Trompe l'oeil. Acrylic on birch plywood, 19-1/2 x 33 x 2-3/4 inches

AF: How do you construct the pieces?

RI: A lot of Elmer’s carpenter’s glue...it’s very high tech [laughs]. Basically the garment or leaves, or whatever object it is, is pinned up to a Styrofoam board gridded off into one inch squares. It’s always a 1:1 relationship, I’m always looking at something. Then on paper gridded off in one inch squares I make a contour line pattern, just an accurate drawing of where all the edges are and the shapes involved and then I start making tracing paper patterns based on that and looking at the garment or object, trying to analyze it in terms of planes that I can saw out and join together to make a surface. A large piece may take hundreds of pieces of wood, a dress for instance.

If you get enough pieces of wood going you can build about any surface. They’re layered various ways. They aren’t carved, there are no knives or chisels involved, but there is a lot of sanding, which is a form of carving, I realize. But I’ve never learned to carve. And you don’t carve plywood easily anyhow. My strategy is to build as much of the surface as I can without making myself crazy and then to rely on the paint to carry the rest of the illusion.

I very much enjoy the fusion and confusion of real and illusory form. So part of it is actual form, which is where I have a leg up on the old trompe l’oeil painters, and the illusion of form I get from color and value changes and details that are painted on that. I use acrylic paints, I couldn’t possibly deal with the drying time of oil. This means I’ve had to develop some drybrush techniques and other techniques to be able to blend smoothly because you can only do so much wet into wet. Actually I do very little wet into wet. This is not the way I was trained to paint, I was actually a fairly painterly painter using oils until 1967. I’m still painterly because I see painterly. You can’t see a lot of brushwork in my pieces, but I’m not afraid for you to catch me painting. I’m not trying to completely hide the presence of a painter.

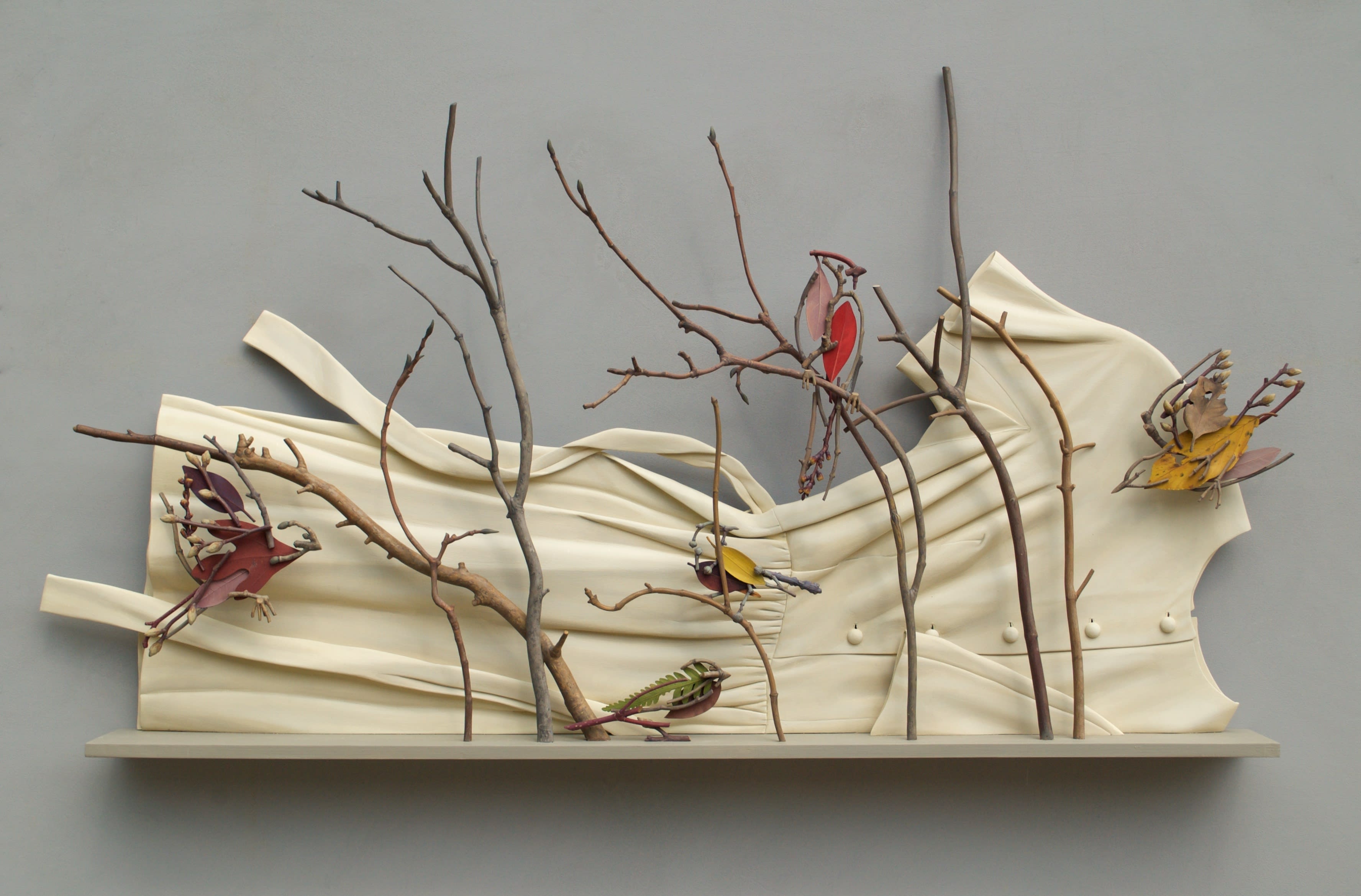

Ron Isaacs, PASSERINES, Trompe l'oeil. Acrylic on birch plywood, 23 x 42-3/4 x 6 inches

AF: What is your favorite tool?

RI: That would be a scroll saw, which allows me to make whatever shape I want. The only tools I really use are a scroll saw and a belt disk sander and a Dremel that I use with a ½ inch sanding drum. Mostly the scroll saw and the belt disk sander. I use about a #3 blade on the scroll saw.

One of my main strategies is to set up something as being real and then violate it. I’ll find a way to interrupt it or create a metamorphosis or a transformation of some sort to make you go back and say wait a minute, how did I get here and question the reality of it.

I don’t consider myself a woodworker, truly, because I’ve never been into the romance of wood. Wood is sort of a friendly mystery, but basically I’m trying to make a surface to paint on. And the wood is all covered up. Before the pieces are painted they aren’t bad looking relief sculptures, actually.

Ron Isaacs, LITTLE SISTER, Trompe l'oeil. Acrylic on birch plywood, 32 x 22-3/4 x 3 inches

AF: Do they always hang on the wall?

RI: Yes. I guess I’ve done one or two pieces that didn’t have a back side but you can’t go all the way around. That would make me nuts completely to try to deal with an object in the round. One nice thing about garments is they stay close to the wall and present a surface that I can actually construct. I never made it all the way to 3 dimensions, I’m a 2.5 dimension artist.

Ron Isaacs, COUPLES, Acrylic on birch plywood construction, 8 x 8 x 1 inches

AF: You mentioned the first piece you did was your raincoat. Does that mean you always have a reference garment in front of you?

RI: Yes, that’s right, and I worked my way finally to trompe l’oeil because I like the authority that it gives the work. The authority of something seen directly that becomes convincing. I’m not actually fully committed to or terribly interested in the trompe l’oeil part of it. It’s just my way of making an image and the image is the important thing. It’s just to give the image authority. I think a lot of trompe l’oeil paintings…while I can be entertained by them, it isn’t terribly deep. It’s mainly a demonstration of skill, I think. You do get some surprising and remarkable and impressive images that way but I’m not that interested in just demonstrating technique. I’m trying to make a strong image.

I was trained as a formalist. When I was in grad school we didn’t talk about content much, we talked about the formal elements. We talked about composition and things like that, and that’s still the major element in the work to me, what it’s doing visually. I’m very concerned with shape and negative space, with color and form in general. If I can get an interesting—I don’t know if I like the word interesting or not because it has a reputation as being sort of a weak word, but sometimes it’s the best word—I’m trying for an interesting image, a strong combination of visual elements that presents itself in a striking way. After that I’m very lucky if I can make something with a good degree of psychological resonance as well. Something that’s evocative.

I think my job is to make an interesting object that’s as evocative as I can make it that draws responses from the viewer without being pretentious about it. I find that the more I talk about content the worse it gets in general, so I’m better off to present the work and let the viewer bring what they will to it, and get what they will from it. I know that’s sort of a cliché of contemporary art, you know the open content idea where I bring my life to the work and now you bring yours. It sounds terribly corny and pretentious. But you know, your experience in front of a work of art is yours. I try not to mess too much with it. I present something that could have a number of readings, and probably can’t predict what you will get from it.

AF: Thank you for talking with me today.

Momentum Gallery proudly represents Ron Isaacs' work. Stop by to see his marvelous painted constructions at the gallery in Asheville anytime and at CONTEXT Miami, December 4-9, 2018. Please contact us if you'd like to attend the contemporary Miami fair – we are happy to provide you complimentary passes.

-

ARTIST PROFILE: SAMANTHA BATES

Samantha Bates has a solo exhibition August 30-October 31, 2018 Samantha Bates, Reach Toward the Pacific, Acrylic, colored pencil, artist penon unstretched primed canvas, 52-1/2 x 48 inches

Samantha Bates, Reach Toward the Pacific, Acrylic, colored pencil, artist penon unstretched primed canvas, 52-1/2 x 48 inchesDr. Alysia Fischer (AF) interviews Artist, Samantha Bates (SB). Alysia Fischer is an author, artist and anthropologist who lives in Weaverville, NC. She received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of Arizona and her MFA from Miami University (Ohio). Her research on crafts includes the books Hot Pursuit: Integrating Anthropology in Search of Ancient Glassblowers and Myaamia Ribbonwork (co-authored with Andrew Strack and Karen Baldwin). Alysia is also an accomplished maker, as both a glassblower and metals artist.

AF: Did you always know you were going to be an artist?

SB: My family had a lot of makers in it. My aunt does cross stitch and quilting, we used to do all these projects together and that's where I made a gift for the first time. I followed the instructions for a little napkin angel. I remember doing all the stitches and painting the face, then giving it to my mom. Every stitch was a record of my time and care. Those early experiences in making art and building gifts and doing fiber work with my family came into my practice later. But I actually fought being an artist pretty hard, even though I loved to do it for myself and I went to an arts high school. I knew that I loved to do it but I also didn't know any artists. There wasn't an artist in my family, I didn't know any. I didn't know if it was reasonable. We were a family of worker bees, you know. You take care of your family and above all you go for security and food and shelter. You get a job. If you go to school it's directly to get a job.

The idea of being an artist was just unfathomable to a fundamental part of who I was. But I couldn't not do it. I was at University of Washington for one quarter without any art classes and it was like I was completely stifled. I couldn't see my life going that way. And then the next quarter I changed my major to Painting/Drawing and I never looked back. I also think how completely lucky I am that at 18 I found something that I could do for 10 hours a day and wake up and be excited to go back to. How many people have that?

AF: How did you arrive at your distinctive style of mark making? I've seen some of your work with marks made with pens and markers and pencils and other work with embroidery and other sewn marks.

SB: The work crosses a lot of mediums in the sense that it has drawing, painting, fibers--and even within fibers there's coiling and there's machine sewing and hand-stitching. I think an umbrella that covers all of it is repeated mark and care. I wanted to continue to grow so I started asking, 'What's the hard thing that I can tackle next?' 'What's the challenging thing that I'm not sure I can do but I'm really excited about?'

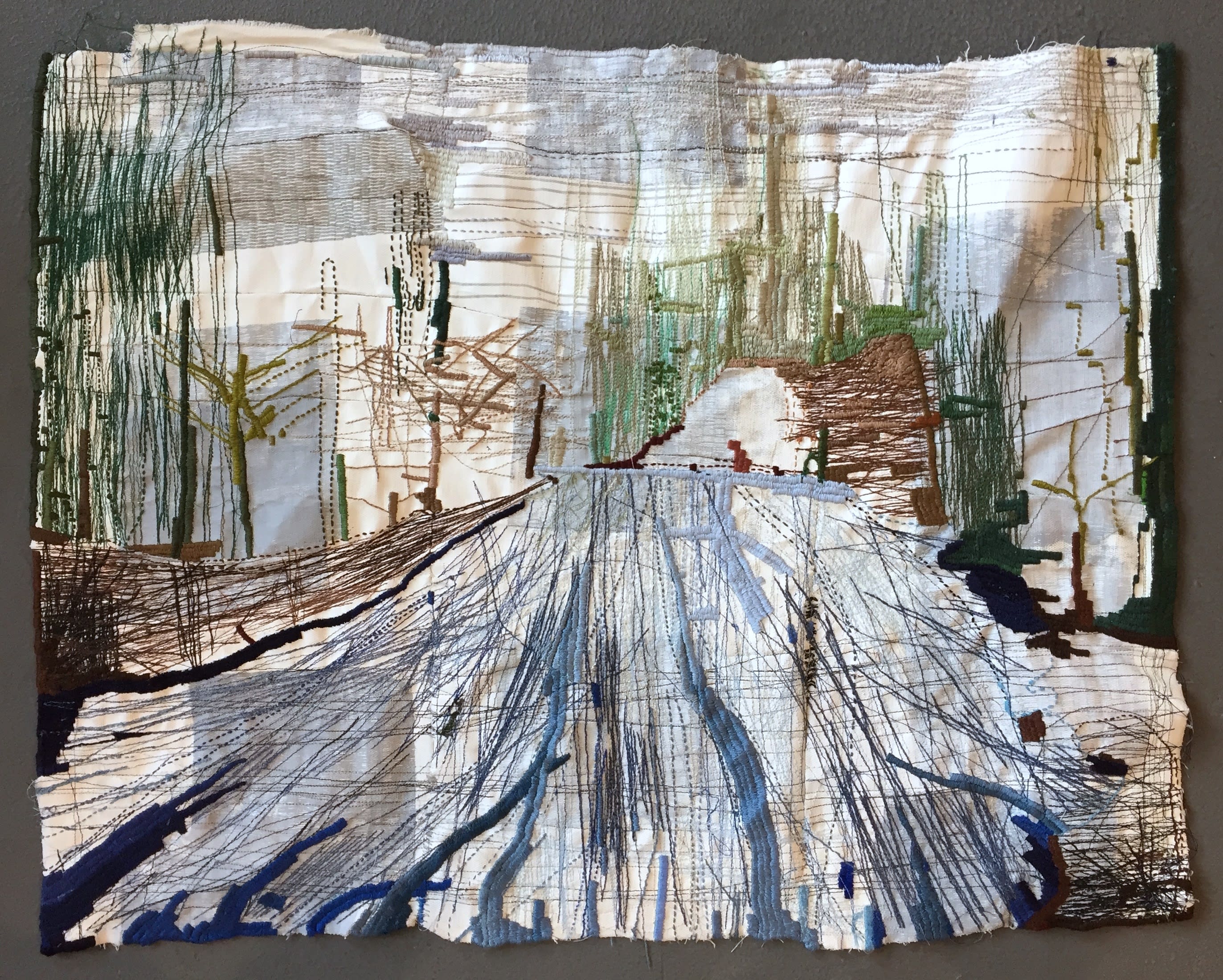

Samantha Bates, Home, Stitch, Walk, Pen, screen print, machine sewn thread

and hand sewn embroidery thread on un-stretched primed canvas, 22 x 28 inches

And that's when I started the piece Reprise that's in the show. It's a really important piece for me. I didn't know if I could do it. It was nine months of focusing on one piece--which is not how I usually work--and it's hundreds of thousands of small dashes building to this imagery. The imagery comes from when you look out on the ocean of Washington and the tide has gone out and there are all these little pits in the sand that have collected water but are reflecting the light and the sky and the water. It's not strictly representational, it's abstracted, but that's where it comes from. And then there's the tide going in and out and the repetition in that and the repetition of the marks. Hundreds of thousands of dashes. It all felt like it really came together-the nature that is so important to who I am and where I live. It's in the work in a visual way, it's in the work in how I move and how I make the mark. The repetition just clicked; it became an essential part.

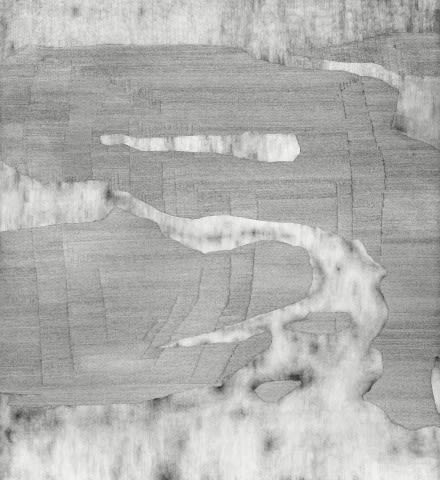

When I put Reprise on the wall, after working on it on a table, I didn't really know what it was going to be. I put it up and everything went silent like the on the Fourth of July when a firework goes off and everything else gets kind of quiet for just an instant. That happened. And it was such an important moment for me. I felt like I had really found something. I also realize the repetition and the mark came from a memory that I have of my grandma. My Oma passed away when I was in 5th grade but we were really close. I was her youngest of many grandkids and she'd come over to the house and we'd all get our little moments with her. My parents had this deep rug in the living room, which was a quiet room with no tv. You don't eat there. It's where guests come. My Oma liked it because she didn't like to be near any of those things. We'd sit on this plush rug and we'd kind of sink into it and straighten out the fringe. And she would say, 'How did you sleep little one?' and we would do that practice every time she came to visit. I was in grad school and trying to figure out where the repetition in my work came from. I knew the small subtleties that happened were fascinating to me. I couldn't get away from it, it was such a part of my practice. I think it stems back to those memories with my grandma and that physical action, and stitching with my aunts. Repetition in fiber work and repetition in the drawing are all the same. It also ties back to the gift giving so it's about care and labor and time and landscape. Samantha Bates, Reprise, Pen and pencil on stretched primed canvas, 65 x 61 inches

Samantha Bates, Reprise, Pen and pencil on stretched primed canvas, 65 x 61 inches

AF: You mentioned working on the pieces while they're flat, is that always the case or was that just the one piece?

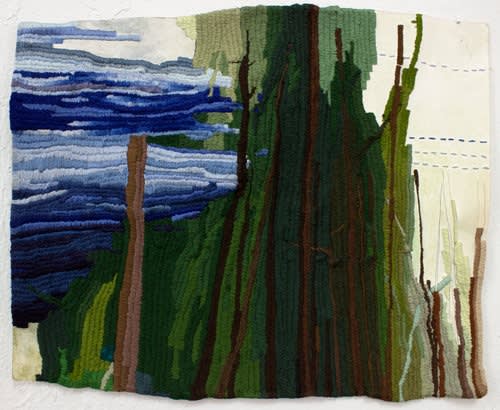

SB: It depends. Oftentimes I'll go between the two. I'll have a large table in my space and I'll work on it on a table for a week and then I'll put it up on the wall and work on it for a week. I think it's important to have both experiences. There's a tree fibers piece, Home Stretch Grow that's like 14 feet. That was constructed mostly on the ground and handstitched together. And a lot of the fiber pieces are constructed in a seated position and they feel much more intimately connected to comfort and coziness.

Samantha Bates, Stretch, Grow, Shelter, Yarn, thread, and cotton piping cord, 16' 4" x 10' 6

AF: Your works are quite large, what is important to you about the scale?

SB: I have 4 or 5 smaller pieces in the show as well. But I do really enjoy working large. I think that part of it is that I spend so much time on the work and the labor is so important to the repeated line. The larger scale allows me, and hopefully the viewer, to enter into it. It's an engulfing kind of feeling. I also think something beautiful happens with the marks where when you approach the work your experience changes. So from 10 feet away it's a landscape and then from 5 feet away it's hundreds of thousands of marks becoming abstracted and then up close maybe it's a landscape again and you get to change how you understand the work. And the second time you see it it's not like the first. I love to play with that and reward the viewer for their extended time and attention and I think sometimes there's something different about approaching a work that's larger than you and how you can feel in front of it.

AF: You mention your work draws upon the imagery of your native Washington State. How were you impacted by living in Boston [for graduate school]?

SB: It had a huge impact on my practice in general but especially this show. Up until I was 25 I lived in Washington. I had this [West] coast connection. When I was upset, when I was happy, I would go out into nature, I would go hiking, camping. It was where I thought, it was where some of my happiest memories are. It's a huge part of who I am, but then I moved to Boston. The dislocation of that was bodily. I felt isolated and separated from it. And the work called home as much as I did. Sometimes it was a comfort to me, sometimes a celebration, sometimes it was mourning.

The dislocation and separation, the yearning for home. The work was really how I visited and found that place, a shelter for me. Now I'm reveling in my reunion and so happy to be so close to those places again. Being able to go out and experience and go back to the studio and remember specific details of how your feet feel when you step into dirt. In the winter it can be hardpacked or a little bit damp and squishy and things smell differently and the sound is different. Can I bring that into the work? Can I bring the specificity and richness into the work? There's a piece, Winter's Mist, in the show. Western Washington has this dense cleansing air in the winter. It's like after it rains or everything is snow-covered and everything smells clean. It's cold but it feels like a specific, beautiful thing. I'm trying hard to find that light and that air. I like to pursue those kinds of feelings. Samantha Bates, Winter's Mist, Acrylic, gouache, colored pencil, and inkon unstretched primed canvas, 43 x 33 inches

Samantha Bates, Winter's Mist, Acrylic, gouache, colored pencil, and inkon unstretched primed canvas, 43 x 33 inches

AF: What has it been like to work with Momentum Gallery?

SB: It's been amazing. I feel grateful and happy. I trust Momentum and they trust me. I tell my friends I'm so lucky and I can't believe it and I'll list like 20 things that are amazing: Jordan is so smart and intuitive and considerate. When he talks about the work he gets it and he's interested in it and he's been thinking about it and he's invested in you. And that's amazing. And even just the little things about pricing and framing, everything is fair and ethical and being able to trust that. I'll think 'Sam, you're lucky and it's amazing that you found each other but also you worked for ten years so when that opportunity came you were ready for it.' So there's a gratefulness, but also a pride that when an opportunity like this came to me I was ready to take advantage of it.

AF: Thank you for talking to me today.

SB: Of course.

Samantha Bates, Lean Into the Winds, Embroidery thread hand sewn into paper, 10.5 x 13.5 inches

-

Artist Profile: Jennifer Halvorson

Halvorson appears in Reflections through August 25th Jennifer Halvorson, Elapsed Retreat (detail), Blown and cast glass, tatted raw silk, 13 x 3 x 3-1/5 inches

Jennifer Halvorson, Elapsed Retreat (detail), Blown and cast glass, tatted raw silk, 13 x 3 x 3-1/5 inchesAlysia Fischer (AF) interviews Jennifer Halvorson (JH) and shares that with our collectors:

AF: Thank you for taking time to speak with me to today. Did you always know you were going to be an artist?

JH: Not always. I can’t say that when I was a child I thought I would be an artist, but I was always involved in art and making things. Part of that came from my family making sure I was exposed to different crafts or taking me to visit really nice craft shows, museums, and exhibits. That interest continued through school. I definitely didn’t always think ‘I’ll be an artist,' but you just follow different interests and what drives you. There’s that whole saying of ‘I don’t want to feel like I’m working.’ When you love what you’re doing, you’re not working, really.

AF: You’re trained in both glass and metals. Do you consider yourself a glass artist, a metals artist, or a mixed media artist?

JH: I’d say mixed media. My BFA is in both glass and metal. In that program, we were taught to understand technique and craftsmanship, but we were also encouraged to experiment with other materials, so bringing glass and metal together was really great. I received an MFA in glass specifically, though I’ve always kept my hand in the metals studio.AF: Some of your work has incorporated the notion of repair while other work seems to alter forms in ways that subvert their original use. I’m curious about what draws you to these themes of repair and transformation or intervention?

JH: A lot of times the objects I’m using are found. The objects are very specific, so there are rubber molds being made and then manipulation from that. With this kind of plain object, my goal is to evoke a certain emotion or convey some metaphor or symbolism through the object, so they need to change or transform in connection to the idea. In the beginning, I’ll have a specific concept I’m trying to include. Then the pendulum swings and I’ll want to put in more of a feeling. This is how I hope to connect to a wider audience. I’m taking this object, maybe a very nostalgic or common object or material and then trying to imbue an emotion or storyline that’ll connect with the viewer.There is another body of work that’s about mending and repairing. I see two sides to that. Sometimes the objects are being stitched up or wrapped up and it might have more of a distressing look. Other times it’s about form where it’s meant to hold light and have some breadth to it. I’m thinking particularly about the knitwork. In terms of the transformation of the jelly jars, it’s more narrative because I intend the objects to represent people without any imagery of a person. That’s to make the work more accessible and open it up to the audience to insert their own father figure, or mother, or uncle, or sister…whoever is in the realm of the narrative. Also, with the jelly jars, a lot of people have associations with canning and preserves, whether it be with family or at the farmer’s market and they connect to that experience. By pushing the jars with cutlery, it activates the objects with a presence of that remembered person or activity.

Jennifer Halvorson, Perfect Influence, Blown glass, tatted lace, found objects, 9-1/2 x 9 x 6 inches

Jennifer Halvorson, Perfect Influence, Blown glass, tatted lace, found objects, 9-1/2 x 9 x 6 inches

AF: A lot of your work references memory. How do objects relate to memory?

JH: They become symbols to us. Objects remind us of a past time, or a past person, or a past experience. I’ve been researching memory for a long time. I’m really intrigued by the idea that you’re not going to remember exactly how something was, or the exact truth, and everyone’s perspective of the same situation is going to be slightly different. But the things that bring you to that memory are these objects that we surround ourselves with, and they kind-of piece together who we are. You collect objects because you want to remember this person or visiting that place. ‘I will have this object and it will be the symbol of this time and of this feeling’. It can be happy or sad, or often bittersweet.

When I first began exploring the concept of memory it was connected to the idea of people starting to lose theirs, and how memory is your identity. And that was really the start of how my work has evolved, because in undergrad I was using medical diagnostic imagery in my work. In grad school it became a totally different focus and slowly evolved from there. At first it was very specific and how memory works and how a culture and a community come together because of all these joint memories that we have that we can connect to. The work tried to get less specific, more about shared human experience, experiences I remember, lessons, and emotions that other people go through as well. A bit of poetic therapy, I guess.

AF: Your art practice includes researching the objects you’ve found or object types you’re reproducing and manipulating. Can you tell me more about that process?

JH: I think it’s important to know the history of things you’re working with. Why they were produced, what was their function, and how did that connect to people? I think it’s really important to know. As far as how I collect things, it comes from growing up. My family is really interested in antiques. Going to look at objects in different antique stores, you look for the unusual and figure out what it does and its storyline. There’s a fair amount of objects I find I’m drawn to because of their history or the way they evoke a time past. My family has a lot of items from a few generations ago, so you get those stories. You’re looking at an object and being told a story of a great grandmother. And so, this object represents a person, and how do you take that object and relate that story or that connection that you have to that person? Usually I’m not using objects that are within my family, but rather items where I come up with stories.For example, I have a series of work titled Thirst, which is these glass teacups with bronze chairs inside them, set upon an ornamental bronze saucer. That idea came about from childhood peekaboo cups. Parents used these with children first learning to drink from a cup. There’d be a little picture at the bottom or a little figure. ‘If you drink all your cup you’re going to get to see Pooh Bear’. I just really loved the design and the function of that object and what it was meant to do as far as encouraging that child. At one point I decided I wanted to make that sort of connection with the adult. What would the adult peekaboo cup be? So, I started thinking about gathering up some different adult teacups and what you would want to see. What would adults desire to see? What would encourage you to get to the bottom of this cup? And then I was researching chairs and the history of chairs and the idea of how at first they were showing ‘authority’. Not everyone was able to have a chair. Having a chair at the table. The idea of a comfortable chair. The stability of the chair. The idea that you have a favorite chair. It all comes back to stability, home, and comfort. So, I was looking at the different designs of the different chairs and trying to imagine their designs with the teacups. It can be a roundabout way of seeing how everything comes together, sparks of concepts or stories or ideas from having looked at objects constantly.

Jennifer Halvorson, Genuine Relation, Blown glass, cast bronze, found objects, 6-1/2 x 10-1/2 x 6-1/2 inches

Jennifer Halvorson, Genuine Relation, Blown glass, cast bronze, found objects, 6-1/2 x 10-1/2 x 6-1/2 inches

AF: Your website includes a quote by a French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. Are there particular writers who have been influential to thinking about artmaking?

JH: There were quite a few during grad school, when you’re positioned to be reading through a lot of different works. I enjoy Gaston Bachelard’s writings—which can be thick, but you can pull so much meaning from every word—his thoughts about how memories are connected to home. Truth is, a lot of my work is about connection to the home, because even if they’re about experiences, it has that underlying it. A few other authors are Rebecca Rupp, who has written the book ‘Committed to Memory: How We Remember and Why We Forget’ that I recall being really engaging. Sherry Turkle wrote a book about ‘Evocative Objects’—also about that connection, about that need, and why we have these objects around us. I also read a few kind of oddity books. Last year I read the ‘Antiques Magpie’, it’s just a collection of stories and facts from the world of antiques. And then there’s this really good book I read called ‘Art and the Home: Comfort, Alienation and the Every Day’ by Imogen Racz.

AF: What inspires you?

JH: Making. I need to be making something. For example, my daughter is now 7 months old and my art practice has been a bit on hold. And you start to do a little head twist after a while, because you just need to be making. Working through objects and materials, you’re going to come across challenges like ‘How am I going to make this?’ and you become a student again. The material is always humbling. And you have to get more technical with making a mold. And you’re going to have to make three attempts to get what you want and so you have to just continually be making. Because I find, you get rusty too. If I’m in a teaching mode and I have to jump back into a technical mold, I’ll feel a little rusty. I’m inspired to be making and experiment with the material. And some of the pieces with the glass and metals are bringing me into different studios. Some of those processes, the repetition of the hand, it’s great, I’m really drawn to it. It can be really tedious and exhausting but it’s also relaxing and rewarding.

AF: What inspired the pieces in the upcoming Momentum show, Reflections?

JH: Jordan Ahlers talked to me about Reflections in connection to Biltmore Estate and the Chihuly exhibit that was going to be on display this summer. It was perfect timing because I was visiting Asheville when this discussion was happening and already had plans to tour the Biltmore. After having that tour and thinking about my work, I was interested in proposing to him two different series. One that was more connected to the idea of the upstairs and one that was more connected to the downstairs. Because they’re totally different settings and story lines that are connected in this one building. Two of the pieces are elaborate door plates that have a blown glass doorknob that is covered with tatted lace and dangling down from the doorknob is a bit more lace and some cast glass keys. The two pieces have different compositions but they’re both highly elaborate, they have the architectural feeling of the “upstairs” of Biltmore. And when I made the pieces they were the idea of someone’s memories and looking into the past and someone’s memories are highly embellished. People remember them differently from one another. They’re also forgotten. These different door plates and door knob compositions represent different pasts or experiences that have occurred and the padlock key is how we remember it. But in the sculpture, there’s no keyhole, symbolizing that can’t get back to that time to know the precise truth that is behind it. It kind of has a maze feeling, which I felt walking around Biltmore Estate had to it. The other series are some canning jars that aren’t found objects. They’re jars I’ve made, blown or casted out of glass, or bronze, or iron. And those compositions are portraits of people and have different narratives. They have a connection to the downstairs of the Biltmore. When I started collecting jars, I was researching them and the different companies and different branding, the idea of the Perfect jar, the Genuine jar, the Supreme jar, all these words and so I went through the rubber mold process to take away some words and leave adjectives to help give more of the narrative to the piece. So the words were originally used by the company for marketing, and now I’m using them to provide more information about the narrative behind each one.I'd like to add - I am so excited to have representation in an Asheville art gallery and to be showing my work with Momentum Gallery is a real privilege!

AF: What are you excited about right now?

JH: There are a lot of transitions for me right now. Part of that is our new baby, and my husband and I just bought our first house. My colleague (at Ball State) and I are looking to teach a glass industry course which will survey from the mid-19th century to today. So we’re going to actually incorporate the press machine into a special topics seminar and also work with a community partner about how current glass engineers and designers work with production, because Indiana has a lot of glass history and still has an operating glass factory. I’m excited to continue to promote my work. I’m really happy to be connected with Momentum Gallery and the show. I’m excited to see how everything works. I think there are a lot of great plans at Momentum. This spring I’ll be going down to the Southwest to talk to two Glass Alliances. Next summer I’m going to be teaching an intensive workshop for Bullseye Glass. It’s just another way to reach out to a bigger community and a different teaching environment. Intensive workshops can just be so different than a semester class. Jennifer Halvorson, Good Luck Disposition, Blown glass, cast iron, found objects, 18 1/4 x 4 x 4 1/2 inches

Jennifer Halvorson, Good Luck Disposition, Blown glass, cast iron, found objects, 18 1/4 x 4 x 4 1/2 inches

AF: Thank you so much for talking with me today. I really like your pieces installed in the show!

JH: Thank you for speaking with me. It’s really nice to talk about the art world.Of special note: Jennifer Halvorson recently appeared in This is Colossal! Here is a link to her interview: http://www.thisiscolossal.com/2018/06/vintage-canning-jars-jennifer-halvorson/

Additionally, Jennifer was also featured in This Week in American Craft, published by the American Craft Coucil: https://craftcouncil.org/post/week-craft-june-13-2018

Alysia Fischer is an author, artist and anthropologist who lives in Weaverville, NC. She received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of Arizona and her MFA from Miami University (Ohio). Her research on crafts includes the books Hot Pursuit: Integrating Anthropology in Search of Ancient Glassblowers and Myaamia Ribbonwork (co-authored with Andrew Strack and Karen Baldwin). Alysia is also an accomplished maker, as both a glassblower and metals artist.

-

Artist Profile: Thor & Jennifer Bueno

Bueno work appears in Reflections, July 1 -August 25, 2018

Thor & Jennifer Bueno, Water Cairn, Sand-etched blown glass, wood, steel, 60 x 18 x 13-1/2 inches

Alysia Fischer is an author, artist and anthropologist who lives in Weaverville, NC. She received her PhD in Anthropology from the University of Arizona and her MFA from Miami University (Ohio). Her research on crafts includes the books Hot Pursuit: Integrating Anthropology in Search of Ancient Glassblowers and Myaamia Ribbonwork (co-authored with Andrew Strack and Karen Baldwin). Alysia is also an accomplished maker, as both a glassblower and metals artist. Below, Alysia interviews glass artists Thor & Jennifer Bueno.AF: Hi, Jennifer & Thor. I am intrigued by your work and partnership. What drew each of you to glass?

Jennifer: I was in college at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), majoring in Industrial Design because I wanted to do special effects for movies. When I was coming along it was about model making and all the fun stuff like puppetry. I’ve always been fascinated with otherworldliness and fantasy. After the first semester in Industrial Design I realized that it was not my bag. We were doing engineering drawings of milk cartons and having critiques for four hours about it. That was the major if you wanted to do special effects, but I was coming along in the 90s when everything was shifting to computers. I realized I wouldn’t actually be making stuff and I wanted to be the maker. I didn’t want to do a drawing and send it out for someone else to make the thing, so I switched to majors. There was an Industrial Design class that did a lighting semester. I saw that exhibit and thought ‘This glass is really beautiful’. It had that same otherworldly feel, that light through the glass. It was just so alien and magical looking to me. Then I wandered into the glass studio, and that’s how I ended up working in glass.

Thor: That’s easy. It was more fun that surfing. What kept me in glass is that it’s still more fun than surfing. There’s a whole stock answer about the spontaneous moment of clarity, the meditation. All that stuff is true. It’s difficult for me to focus on one thing. I get that clarity and that calm from glassblowing. It involves every part of me simultaneously, physically as well as mentally. I started blowing glass in 1979. My instructors at the junior college were all potters so they were really good potters and they knew how to build a glass studio because of pottery. As far as blowing glass was concerned, they didn’t have a clue. So, my instruction was, ‘Lips on this end, glass on the other, and figure it out.’ That’s how it was for me for the first seven years. I started in ’79 and then I went to Pilchuck in ‘86 for the first time and then pretty much relearned everything the Venetian way.

Thor & Jennifer Bueno, Looking Glass, Blown Glass, 48 x 84 x 3 inches

Thor & Jennifer Bueno, Looking Glass, Blown Glass, 48 x 84 x 3 inchesAF: Can you tell me about the dynamics of your artistic partnership?

Jennifer: Thor is really high energy. He’s one of those people who doesn’t slow down, doesn’t stop. So, glass really suits him that way. Thor is just like ‘Do it.’ It’s great because he has that momentum, always moving forward. If he didn’t have me he’d be all over the place, and if I didn’t have him I’d just be staring at my navel and not moving. Glass is a funny thing. That’s one of the challenges I’ve had, the struggle like jumping off a high dive. You’ve got to commit. You’ve got to be in that moment, which is wonderful, but my nature is more that I like to sit and look and change. So, with our Bueno Glass stuff, that’s how it really works. He’s out cranking in the hot shop. The nice thing is that these forms are so fitted to Thor’s personality. There are glassblowers who are goblet makers and make a lot of components and hot sculpt them together with torches and they spend hours on one piece, and that’s not Thor. He’s all ‘Get it hot and spin it, and let it go, and do it again, and do it again…’ We’ve really seemed to find a way of working that matches our personalities. I’m in a different studio doing drawings for proposals, and I’ve got all the pieces organized into color sets. For all of our wall pieces, we do templates. So, I’m doing templates and I’ll go down to the hot studio and say we need a range of this color. Thor says that he makes the brushstrokes and I make the painting. We do blow glass together for R&D, like if we need to find a new color. We’ll talk and get ideas and troubleshoot stuff and, in that case, we work together in the hot shop. We both enjoy doing that kind of thing and it works.

Thor: Jennifer can do anything, she’s so freaking smart. She won’t brag about it, but she got two MFAs in three years. One from Bard, where it’s all about thinking, and then one from Alfred where it’s all about making things with your hands, and she kind of did both in three years. Over the last decade she’s gotten so good at making those compositions. Because there’s so many thousands of micro-decisions involved in the relationships between the pieces-the big shapes, little shapes, the patterns, the negative space, the colors, it just goes on and on. Jennifer works really hard to make it look effortless. She creates in a very contemplative way; she’s very thoughtful. She comes from the RISD mindset where you think about the thing for 45 minutes and then you take 15 minutes to do it. That’s the ratio of thought to work. It’s a good thing, but that’s not really me. I’m super frenetic and can’t go slow. That glassblowing thing fits well with me. I work superfast and really hot and I enjoy it when the piece is about to drip off my pipe; I can make something better out of it when it does that. That aspect of our partnership is really great because she does the meditative part where (as Jennifer mentioned) she creates the painting out of my brush strokes.

Jennifer Bueno views Gilded Azure, Blown Glass, 84 x 84 inches

Jennifer Bueno views Gilded Azure, Blown Glass, 84 x 84 inchesAF: What can you tell me about the piece, Gilded Azure, that will be in the upcoming Momentum show “Reflections”?

Jennifer: We had this problem of making big installations where you can’t really see the details of things. Many of our bigger pieces have been in awkward spaces, because that’s one of our strengths. We can do these pieces in a hospital where there’s a narrow strip or strange space, but it’s really tricky to get a good photograph. We’ve been making these new metallic pieces that are a hybrid of the silver and the stone. I was playing with the different compositions and started making circles. It was nice because you could see the form and see that each stone was different and see the colors. When we heard about the Chihuly exhibit, you always think of Chihuly glass of having such a presence. And it’s not just because they’re big but they just have this presence of being almost otherworldly. We were inspired by that and thought it would be nice to make a piece that would be big enough that you could enter. You can see it as one thing, so it’s like a meditation. You can enter it visually.

As far as Biltmore, when I think of it I always think of the Gilded Age. Gilded seems like an appropriate word for Biltmore Estate. The blue in the piece reminds me of North Carolina, the sky and the water and the river stones. It all comes together into one atmospheric space. The vein of gold running through Is reminiscent of a river but also a blue stone with a vein of gold. I think of Biltmore as this sort of gilded thing in the middle of the wilderness. There’s this natural place but you also have this glittering object, something precious and rare, running through it.

Thor: The big concentrated dot is a bit of a departure from our usual work. A lot of the compositions we make are customized to fit very specific parameters. Typically, our work lives on the architecture and is kind-of growing there. This new direction is more like a piece of jewelry that can be anywhere. A giant brooch, like architectural jewelry, something you wear. And that becomes like a Chihuly chandelier being a giant pair of earrings for a building. And I think that’s where we are trying to go.

Jennifer Bueno and Jordan Ahlers, Gallery Director, at Momentum Gallery's Grand Opening, October 2017AF: I really appreciate you talking with me today.Jennifer: Cool, thank you.Thor: Thank you so much for your time.

Jennifer Bueno and Jordan Ahlers, Gallery Director, at Momentum Gallery's Grand Opening, October 2017AF: I really appreciate you talking with me today.Jennifer: Cool, thank you.Thor: Thank you so much for your time.

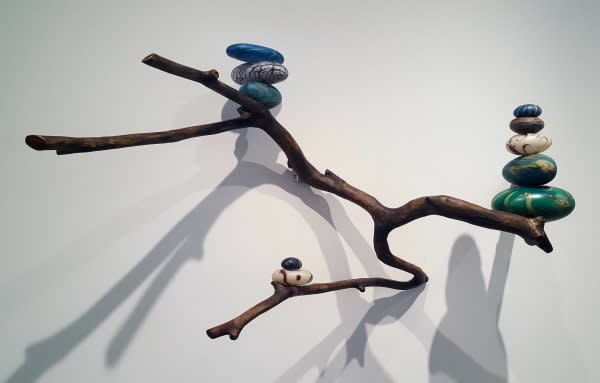

Thor & Jennifer Bueno, Zen Branch, Sand-etched blown glass and wood branch, 31 x 65 x 17 inches